Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia

This information is about lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL), a rare type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia (WM) is the most common type of LPL.

On this page

What are lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia?

What are lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma and Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia?

Lymphoplasmacytic lymphoma (LPL) is a low-grade (slow-growing) non-Hodgkin lymphoma. It develops from B lymphocytes (a type of white blood cell) that become abnormal and grow out of control.

White blood cells form part of your immune system, which helps fight infections. One of the ways in which B lymphocytes (B cells) fight infection is by developing into plasma cells. Plasma cells make antibodies. Antibodies are proteins that recognise microbes that are not part of your own body (such as viruses or bacteria) and stick to them. This helps your immune system get rid of the foreign microbes. Antibodies are also known as ‘immunoglobulins’ (‘Ig’ for short). There are five different types of antibody: IgA, IgD, IgE, IgG and IgM.

Under a microscope, the abnormal cells seen in LPL have features of both lymphocytes and plasma cells – hence the name ‘lymphoplasmacytic’.

Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia

The abnormal cells in LPL can produce large amounts of abnormal antibodies (sometimes called ‘paraprotein’). In most cases of LPL, this is an IgM abnormal antibody. LPL with IgM detectable on blood tests is called Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia (WM). It is named after the scientist who first described it.

Around 1 in 20 cases of LPL produce a different antibody (usually IgG), or don’t produce abnormal levels of antibodies at all.

The IgM abnormal antibody produced in WM is a large (‘macro’) protein that can make your blood too thick if too much of it is produced. This is called ‘hyperviscosity’. Other antibodies are smaller and less likely to cause hyperviscosity.

All types of LPL are treated in the same way. We refer to these lymphomas as ‘WM’ for the rest of this page.

Who might get Waldenström’s macroglobulinaemia (WM)?

WM is a rare type of lymphoma. Fewer than 400 people are diagnosed with WM in the UK each year. A WM registry was developed in 2021 to collect ‘real world’ information about people affected by WM in the UK.

Most people who develop WM are over 65. It affects around twice as many men as women. It is more common in white people than black and other ethnic populations.

Scientists don’t know what causes WM. Some infections, inflammatory conditions or autoimmune diseases (diseases that happen when your immune system attacks your own body) such as Sjögren syndrome might increase your chance of developing WM. People who have a family member with either WM, another type of B-cell non-Hodgkin lymphoma or chronic lymphocytic leukaemia (CLL) have a slightly higher risk than others of developing WM. However, the risk is still very low. Most family members do not develop lymphoma.

About 9 in 10 people with WM have developed an acquired mutation (change) in a gene called ‘MYD88’. Mutations in a gene called ‘CXCR4’ also occur in around 1 in 3 people with WM. You are not born with these mutations and these are not inherited. Scientists are studying these changes to find out how they are linked to the development of WM and if they might be used to help treat WM more effectively.

Symptoms of WM

WM usually develops slowly over many months or years. You might have no symptoms at all to start with. Some people with WM are diagnosed by chance, during a routine blood test or an investigation for another condition.

The symptoms of WM can be very variable, even in people who have the same level of IgM abnormal antibody. The symptoms can relate to the LPL cells themselves, but they can also be due to the high level of IgM abnormal antibody in the blood, or complications related to the IgM abnormal antibody. The symptoms are often quite different from the symptoms of other types of lymphoma.

Symptoms related to LPL

Most people with WM (and other types of LPL) have abnormal B cells and plasma cells in their bone marrow (the spongy tissue in the centre of bones where blood cells are made). The bone marrow may then not be able to make as many normal blood cells as usual. This can cause:

- anaemia (shortage of red blood cells), leading to tiredness, weakness and breathlessness

- neutropenia (shortage of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell), leading to an increased risk of infections

- thrombocytopenia (shortage of platelets, which help your blood clot), leading to a tendency to bruise and bleed easily (for example, nosebleeds).

Swollen lymph nodes are less common in people with WM than in other types of lymphoma. However, around 1 in 5 people with WM have swollen lymph nodes or a swollen spleen. A swollen spleen can cause discomfort or pain in your abdomen (tummy).

People with WM can also experience fevers, night sweats and weight loss, which are symptoms of many types of lymphoma. Doctors sometimes call these ‘B symptoms’.

In about 1 in 100 cases of WM, abnormal lymphocytes and plasma cells can build up in your central nervous system (brain and spinal cord). This is called ‘Bing-Neel syndrome’. It is very rare. It may cause headaches, weakness or abnormal sensation, seizures (fits), changes in your thinking processes or abnormal movements.

Rarely, lymphoma cells build up in other parts of the body and form masses or tumours. These are usually slow-growing and cause few symptoms. However, they can press on surrounding organs, nerves or blood vessels. This can cause pain or other symptoms in the affected area.

Symptoms related to abnormal antibodies

Many people with WM have symptoms caused by high levels of abnormal IgM antibody in their blood. This can make blood thicker than usual. This is called ‘hyperviscosity’. Hyperviscosity can cause symptoms such as:

- nosebleeds

- blurring or loss of vision

- dizziness or headaches

- ringing in the ears (tinnitus)

- drowsiness, poor concentration or confusion

- shortness of breath.

If you have hyperviscosity that causes symptoms, it is known as ‘hyperviscosity syndrome’ (HVS).

About 1 in 4 people with WM develop peripheral neuropathy (nerve damage). This might be caused by abnormal proteins or by the effects of the lymphoma cells on the nerves. Peripheral neuropathy can cause tingling or numbness, usually in the fingers or toes on both sides of your body. If it isn’t treated, it can slowly get worse. You might find it harder than usual to write or handle small objects.

In some people, high levels of antibodies cause red blood cells to stick together in the cooler parts of the body such as your hands and feet, the tip of your nose or your ear lobes. This can cause the red blood cells to break down, leading to anaemia. This is called ‘cold agglutinin disease’.

Some people with WM may produce abnormal antibodies that clump together at lower temperatures. These are called ‘cryogloblins’. This can lead to many symptoms, including poor circulation or a rash, especially when it is cold.

Rarely, part of the IgM antibody can fold in an abnormal way to form a protein called amyloid. This can build up in your kidneys, heart, liver or nerves.

Diagnosis of WM

WM is often suspected based on the results of blood tests. If your doctor thinks you might have WM, you have further blood tests to:

- measure your antibody levels

- check for any other abnormal proteins in your blood

- confirm whether any low blood counts (anaemia, neutropenia and thrombocytopenia) are associated with WM or another disorder

- test for any infections

- look at your general health.

You may also have a bone marrow biopsy to look at the types and numbers of cells in your bone marrow. This might be sent to a lab for genetic tests.

You might also have an eye examination. The blood vessels in your retina can become enlarged or leaky because of the high levels of IgM protein in your bloodstream if you have hyperviscosity syndrome (HVS). Doctors can see this by looking in the back of your eye.

If you have been diagnosed with WM and your specialist feels you should start treatment, you might also have a CT scan or a PET/CT scan to assess whether your lymph nodes, liver, spleen or other organs are affected by WM. If you have swollen lymph nodes, you might have a lymph node biopsy.

Waiting for the results of your tests can be difficult but it is important that your specialist has as much information as possible so they can give you an accurate diagnosis and the most appropriate treatment.

Most types of lymphoma are staged to find out which parts of your body are affected by lymphoma. The staging system is based on how many swollen lymph nodes you have and where they are in your body. This system is not useful for WM because the disease is often in the bone marrow rather than the lymph nodes. Instead, you might be given a ‘prognostic score’. The score is based on your age and the results of your blood tests. The lower your score, the more likely you are to respond well to treatment.

Treatment of WM

WM is a slow-growing lymphoma that is treated to keep it under control, rather than to cure it. Symptoms can come and go over time. Most people live with this disease for many years. Your symptoms and test results are used to decide when to start treatment and what treatment you might need.

Active monitoring (watch and wait)

If you don’t have any symptoms, you might not need treatment for some time. Instead, you have regular check-ups and blood tests to check your blood counts and antibody levels. This is called ‘active monitoring’ or ‘watch and wait’. It does not mean there is no treatment for you, but that you would not benefit from starting treatment yet. This saves you experiencing side effects of treatment you do not need. You have treatment if or when you need it.

You might not need any treatment for many years. A few people never need treatment.

Treatment for WM usually starts if:

- you develop troublesome symptoms

- your blood is too thick because of high levels of IgM (hyperviscosity)

- your blood cell counts change: you develop anaemia (low red blood cells), neutropenia (low white blood cells called neutrophils) or thrombocytopenia (low platelets).

Watch Kate talk about her experience of being on active monitoring

Treatment for WM

The first treatment for WM is usually a combination of chemotherapy drugs and the antibody therapy rituximab. Steroids, such as dexamethasone, are also commonly used. Several drugs that work in different ways are used together to give the best chance of controlling abnormal cells.

The exact treatment you have depends on individual factors such as your general health, the results of your blood tests, and the symptoms you have. Your doctor should give you more information about the regimen they recommend, including information about the possible side effects.

Common regimens (combinations of drugs) that may be used include:

- DRC: dexamethasone, rituximab and cyclophosphamide

- Benda-R: bendamustine and rituximab.

Other chemotherapy combinations have been more commonly used in the past, including regimens containing fludarabine, chlorambucil or cladribine. These are used less frequently nowadays, but may still be used in certain circumstances. Gentler chemotherapy drugs such as chlorambucil might be used if you are not well enough for stronger chemotherapy. These drugs can be very effective.

Other treatments may also be used – your medical team should discuss these with you if they are relevant to you. Newer, targeted drugs are being tested for WM and you may be offered a targeted drug as part of a clinical trial.

- Clinical trials of some BTK inhibitors (including ibrutinib) have promising results in people who have not had any previous treatment for WM. Clinical trials for BTK inhibitors (including ibrutinib, zanubrutinib and pirtobrutinib) also have promising results for people whose lymphoma has come back (relapsed) or who have not responded to previous treatment (refractory lymphoma). However, long-term follow-up data isn’t yet available for all these drugs.

- Proteasome inhibitors (for example, bortezomib, carfilzomib, and ixazomib) have been shown to be very effective at treating WM. They are not yet approved for use on the NHS. The regimen with the longest follow-up data is botezomib, rituximab and dexamethasone.

Treatment is given in cycles over a period of a few months. In each cycle, you receive treatment some weeks but not others. The rest periods between treatments allow your body to recover before the next treatment.

If you have high IgM levels, rituximab can temporarily cause IgM levels to increase further, known as an 'IgM flare'. If your doctor thinks you are likely to experience an IgM flare, they might give you chemotherapy without rituximab for the first few cycles to reduce your level of IgM. Rituximab can then be given for later cycles and after chemotherapy has finished.

After diagnosis I was put on active monitoring (watch and wait) which lasted for 6 years. After developing symptoms, it was decided that I start chemotherapy and was treated with RCP (rituximab with cyclophosphamide and the steroid prednisolone). The RCP managed to give me a partial remission until May 2019 and I then started treatment with ibrutinib. I had a really good response to ibrutinib, which kept my WM under control.

Treatments for symptoms and side effects

As well as treatment for the lymphoma itself, you might need treatment for symptoms of WM or side effects of treatments. This is sometimes called ‘supportive care’ because these treatments don’t treat the lymphoma but support your body through your lymphoma treatment.

You might be given:

- plasmapheresis (plasma exchange) if your blood is too thick because of high levels of IgM (hyperviscosity)

- blood transfusions or platelet transfusions (blood or platelets given through a drip into your vein) if you develop a low red blood cell count (anaemia) or low platelet count (thrombocytopenia); you might need plasmapheresis first to stop your blood getting even thicker during the transfusion

- antibiotics or antiviral drugs to prevent infections if you have low antibody levels or a low white blood cell count (for example, neutropenia).

- immunoglobulin replacement therapy (a drip containing antibodies) if your antibody levels are low and you have had severe or repeated infections.

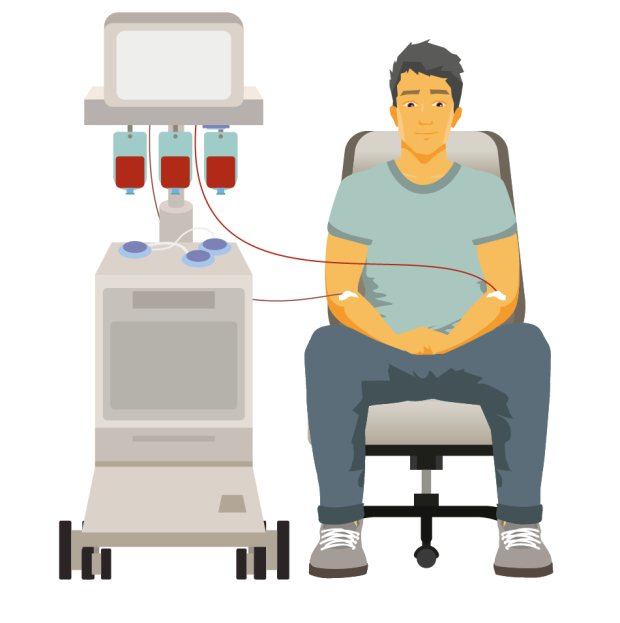

Plasmapheresis (plasma exchange)

If your blood becomes too thick because of high levels of IgM, you might need to have it thinned by a procedure called ‘plasmapheresis’ (plasma exchange). You might have plasmapheresis to keep your symptoms under control, to reduce your IgM levels before starting treatment for WM, or before having a blood transfusion.

In plasmapheresis, a thin, flexible tube called a cannula is put into a vein in each of your arms. Blood is slowly removed from one arm. It passes through a machine that separates the liquid part of the blood (the plasma, which contains the IgM antibody) from the blood cells. The blood cells are then combined with a plasma substitute and put back into your other arm. The whole process takes 2 to 3 hours.

The NHS Blood and Transplant service has a downloadable factsheet on plasmapheresis. Your hospital should also give you detailed information if you need this procedure.

Outlook for people with WM

WM is a low-grade lymphoma that can develop slowly over many years. It is treated with the aim of controlling it, rather than curing it. Although treatment is usually effective, WM is very likely to come back (relapse). You may need treatment from time-to-time.

Your doctor is best placed to advise you on your outlook based on your individual circumstances. They might calculate a ‘prognostic score’ – for example, using the International Prognostic Scoring System for WM (IPSSWM). This score is based on the results of your tests and other factors, like your age, symptoms, and any other conditions you have. Your doctor might use this score to predict how likely you are to respond to treatment.

In up to 1 in 10 people, WM can change (transform) into a faster growing (high-grade) type of lymphoma, usually diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL). If this happens, you might get new symptoms like swollen lymph nodes or a mass that grows quickly. Your doctor can tell you what to look out for.

If your lymphoma transforms to become faster growing, you need a different type of treatment. You can find more information on our webpage on transformation of lymphoma.

Relapsed WM

Although treatment is likely to put WM into remission (no evidence of the disease), it usually comes back (relapses) in most people.

If your WM relapses, you might not need treatment straightaway – instead, you might be put on active monitoring. If or when you need treatment, you might have the same regimen you had before or a different one. Your doctor will work with you to decide what treatment is best for you based on a number of factors:

- how you coped with your previous treatment

- how long it has been since you finished your last course of treatment

- your general health.

The same treatment can often be used again if you have been in remission for 2 years or more. If your WM relapses sooner, you might be given a different drug or combination of drugs.

Some people might be offered a targeted drug called ibrutinib (a BTK inhibitor drug). This can be very effective for people with WM that has come back or not responded to treatment. Ibrutinib is available as tablets. You carry on taking it as long as you are responding to it, unless you develop troublesome side effects.

Some people with aggressive WM that has relapsed very quickly might need a stem cell transplant. This is an intensive form of treatment that is given after high-dose chemotherapy to try to make a remission last longer. It is only considered if you are well enough to have it.

Follow-up after treatment for WM

You need to be followed-up regularly in the outpatient department, usually every 3 to 6 months. As part of your check-ups, you have regular blood tests to check your blood counts and the level of the IgM antibody in your blood. Depending on your symptoms and blood test results, you might need a bone marrow biopsy or, occasionally, a CT scan.

Tell your doctor if you have any new symptoms or if any of your symptoms have got worse.

Research and clinical trials

Researchers are continually trying to find out which treatment, or combination of treatments, works best for WM. Your doctor may ask if you would like to take part in a clinical trial. Clinical trials allow new treatments to be evaluated and compared with more established ones. Studying treatments is the only way that new and, hopefully, better treatments can become available.

My consultant spoke to me about a randomised clinical trial, which meant I couldn't choose which treatment I had and neither could my doctor. I knew the options were the chemotherapy I would have had as a matter of course or a new immunotherapy drug (ibrutinib plus rituximab). So far, indications show that the WM is responding well.

You might be interested in listening to our podcast with Katie, who talks about her story of WM and taking part in a clinical trial.

Treatments that are currently being studied for WM, on their own or in combination, include antibody therapies, proteasome inhibitors, cell signal blockers and immunomodulators. Drugs that target the CXCR4 receptor that is abnormal in around one-third of people with WM are also being researched.

To find out more about clinical trials and search for a clinical trial that might be suitable for you, visit Lymphoma TrialsLink.