Chemotherapy

This information is about chemotherapy in the treatment of lymphoma.

On this page

What is chemotherapy and how does it work?

Chemotherapy and risk of infection

What side effects might I have?

What late effects might I have?

What is chemotherapy and how does it work?

Chemotherapy is a type of treatment using drugs that are 'cytotoxic'. This means that they poison cells. Most lymphoma cells are easily killed by chemotherapy. You can read more about how cancer develops on our separate webpage that outlines what lymphoma is.

Chemotherapy works by doing one or both of the following:

- stopping lymphoma cells from dividing so that they die off

- triggering lymphoma cells to die.

Chemotherapy works on cells that are dividing. The drugs don’t have much effect on cells that are not dividing. Lymphoma (and other cancer) cells divide much more often than healthy cells do. This is why chemotherapy has more of an effect on lymphoma cells than on healthy cells.

This animation explains what chemotherapy is, how it works to kill cancer cells and some of the ways in which it is given as treatment for lymphoma.

How is chemotherapy given?

Chemotherapy is usually given in a number of treatments (‘cycles’). After each cycle, you have a rest period to give your healthy cells time to recover. A whole course of treatment can take between a number of weeks to months.

Typically for lymphoma, you’d have four to six 6 cycles of treatment – it depends on the type of lymphoma you have, your response to treatment and on the chemotherapy regimen you’re having. Quite often, even if you show a good response, you’ll continue with the remaining cycles to ensure that the lymphoma doesn't come back.

You might have chemotherapy as an inpatient (where you stay in hospital overnight) or as an outpatient (where you go home after each treatment).

Chemotherapy is often given with more than one drug. This is known as a combination regimen. Different drugs work on different phases of the cell cycle. Having them together helps to kill as many lymphoma cells as possible.

It’s becoming increasingly common for chemotherapy to be given together with targeted treatments.

Your treatment plan should outline:

- the type of chemotherapy drug or drugs you’ll have

- how many treatment sessions you'll have

- how often you'll have treatment

- how you have the treatment.

I have a type of low grade skin lymphoma and I’ve had three treatments over the past five years, including four cycles of chemotherapy (R-CHOP) over 4 months followed by radiotherapy. My medical team explained that they wanted to give me one cycle of chemotherapy roughly every 28 days. The treatment was successful and I am currently in remission.

You are most likely to have chemotherapy in one or more of the following ways:

- through a tube or injection into a vein (intravenous (IV) chemotherapy)

- by mouth as a tablet (oral chemotherapy)

- by an injection into the cerebrospinal fluid, which surrounds the brain and spinal cord (intrathecally).

Intravenous (IV) chemotherapy

Intravenous (IV) chemotherapy is injected into a vein. This is the most common way to have chemotherapy for lymphoma.

Usually, IV chemotherapy for lymphoma is given through a cannula, a soft plastic tube with a needle inside it. It can also be given through a line (central venous catheter).

To fit a cannula, a nurse or doctor:

- puts the needle into one of your veins, usually in the lower part of your arm

- removes the needle, leaving only the plastic tube in your vein

- puts a dressing on, to keep the cannula clean and in place.

Some IV drugs are given as a ‘bolus’ or a ‘push’ dose. The chemotherapy drugs are injected through the cannula over a short while, usually between a few minutes up to about 20 minutes. Other drugs are given through a drip (intravenous infusion). This is a tube that runs into a cannula into a vein in your arm.

- The IV chemotherapy drugs are mixed with fluid (usually a saline solution) in a bag.

- The fluid drips slowly from the bag into your vein over a set amount of time. This could be anywhere from 5 minutes to a number of hours, depending on the drug or drugs you have.

- The bag hangs from a metal drip stand so that it stays above your arm to allow the fluid to flow downwards. The stand usually has wheels so that you can walk around with the drip still connected to you.

Sometimes, the drip is controlled by an electric pump. This helps to make sure that the chemotherapy drugs flow at the right speed into your vein.

The team delivering the chemotherapy will check that the chemotherapy is flowing through your vein as it should be. However, if you feel any pain or discomfort while you’re having IV chemotherapy, or notice swelling in your arm, it’s important that you tell a member of hospital staff.

Occasionally, the drug goes into the tissues around the vein instead of into the vein itself. This is called ‘extravasation’ and can cause problems if it isn’t stopped quickly. All nurses who give chemotherapy are trained in how to deal with this complication.

You will be given clear guidance by the chemotherapy team at the hospital about how to check the area and what to look out for. You will be followed-up closely by the chemotherapy team who will review the area and escalate for further advice if necessary.

IV chemotherapy through a ‘line’ (central venous catheter)

IV chemotherapy through a ‘line’ (central venous catheter)

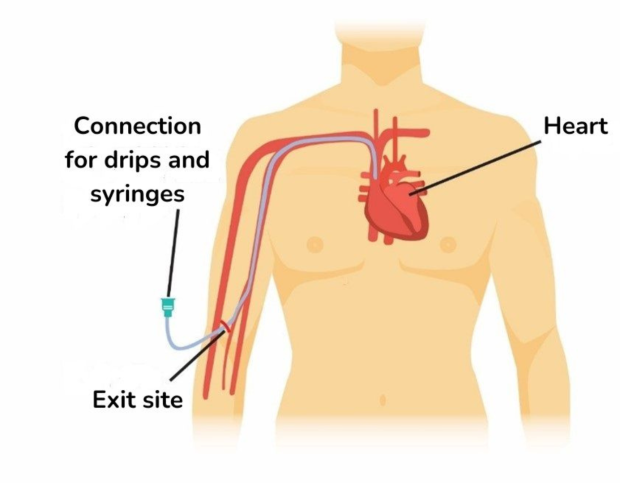

You might have your IV chemotherapy through a ‘central line’ or ‘line’ (central venous catheter). A line is a tube that is put into one of your larger veins, guided by ultrasound. It runs from your chest to your heart.

A line can also be used to give you drugs and other fluids, and to take blood samples more easily than with regular syringes. This can save the discomfort of repeated needle pricks.

Lines are put in during a small operation done under local or general anaesthetic. Once it’s in place, a line isn’t usually painful.

There are different types of line:

PICC line (peripherally inserted central catheter), which goes in through a vein in your arm. The end of the line outside your body also ends in smaller tubes (lumens). It is usually used for short-term treatment or until you have a longer-lasting line fitted, if you need one.

- Tunnelled central line, which is usually positioned on your upper chest. Part of it ‘tunnels' under your skin. You might also hear these types of lines called Hickman®, Groshong® line or apheresis line. You can watch a short video about how a central line is put in on the Cancer Research UK website.

- Portacath (‘port’), which is a thin, soft tube. It runs under your skin and into a vein in your chest, ending in a small disc (port) that goes just under your skin. You’re given chemotherapy through a specialised type of needle – it goes through your skin and into the port each time you have treatment.

Person with a PICC line inserted

It’s extremely important that you tell a member of hospital staff immediately if you feel any pain or discomfort in the arm where your cannula went in. It could indicate that the cannula has been displaced and is now in the incorrect place, meaning that the chemotherapy could leak out into the surrounding area. If this happens, it could cause long-term or permanent damage.

Taking care of your line

Once your line is fitted, it is covered with a protective dressing. You’ll be given information about how to care for it once you go home, including on taking baths and showers while it is in.

You should also be given guidance about how to lower your risk of infection. Even with great care, however, lines can become infected. Occasionally, a blood clot can develop around them.

You might need urgent medical attention to treat an infection. Contact your hospital immediately if you develop any symptoms of infection including:

- redness or heat around the area (site) of the line

- a high temperature (above 38°C/99.5°F)

- swelling of your arm.

Intrathecal chemotherapy

Intrathecal chemotherapy is given into the fluid that surrounds the central nervous system (CNS), which is made up of your brain and spinal cord.

There is a blood–brain barrier around the CNS. It protects your brain from harmful chemicals and infections and only lets certain things reach the brain. Intrathecal chemotherapy is a way of getting through the blood–brain barrier, to let the drugs get directly into the CNS.

You might have intrathecal chemotherapy if you have:

- Lymphoma in your CNS (brain and spinal cord; central nervous system).

- A type of high-grade lymphoma that can sometimes spread to the CNS (such as Burkitt lymphoma, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma with particular risk features) or lymphoblastic lymphoma. In these cases, you might have intrathecal chemotherapy to prevent the lymphoma from spreading there (CNS prophylaxis).

Usually, you have intrathecal chemotherapy by an injection into the cerebrospinal fluid in the lower part of your back. The procedure is called lumbar puncture and is done under local anaesthetic.

Subcutaneous chemotherapy

A small number of chemotherapy drugs are given by injection into the layer of fat that lies just under your skin. Having chemotherapy in this way is known as subcutaneous chemotherapy.

The most usual places to have injections in this way are the skin of the tummy (abdomen), thigh and upper arm. You might be taught to give these injections yourself. If needs be, you could get a referral to a community nurse to give you these injections.

The injection is not usually painful but it might sting for a few moments. The time it takes to give the drug varies from seconds to minutes, depending on what drug or drugs you are having.

As well as chemotherapy, other types of treatment can be given by subcutaneous injection. Examples include maintenance rituximab, growth factors and immunoglobulin replacement therapy.

Ambulatory chemotherapy

Many hospitals offer ambulatory chemotherapy. This means that you don’t have to stay in hospital for your treatment. Instead, you have it in your home or in accommodation near to the hospital. Some people prefer to have chemotherapy in this way as they feel it gives them more independence, privacy and comfort than staying in hospital.

You have ambulatory chemotherapy by a pump-controlled drip (infusion).

If your hospital offers this type of chemotherapy, your medical team will assess whether ambulatory chemotherapy is suitable for you. They consider a number of factors, including:

- your general health, including any other medical conditions you might have

- the type of chemotherapy drugs you need

- your home environment, for example, having family and friends who can be with you while you’re having treatment and offer support if you need it

- whether you can care for yourself and manage side effects.

In case of an emergency, at all times, you will also need to be:

- contactable and be able to contact the hospital quickly, for example, by mobile phone

- able to travel to the hospital you’re having treatment at (usually within about 30 to 60 minutes), otherwise you might be offered accommodation closer to the hospital

- have someone with you who could drive you to the hospital at any time of the day or night, if you need to go.

I was away from home for a long time, initially in ambulatory care, receiving high dose LEAM chemotherapy, and then in hospital once my neutrophils became very low and the side effects too bad. While I was in ambulatory care, we went out for walks and visited museums together as a family. It was quite surreal to be doing that with the chemotherapy attached to me.

Chemotherapy and risk of infection

You have a higher risk of developing an infection while you’re being treated with chemotherapy. It can also be harder than usual to get rid of infections, particularly if you have a shortage of a type of white blood cell that helps to fight infection (neutropenia).

If you develop an infection, you might need treatment with antibiotics to help get rid of it.

It is therefore important that you know:

- the signs of infection to look out for

- who to contact if you think you might have an infection.

If you develop signs of an infection, for example, fevers and generally feeling unwell, you must call your local hotline or other out-of-hours emergency number immediately. You will be advised to attend your local Emergency Department as a matter of urgency to have treatment with antibiotics.

Lowering your risk of infection

While it’s impossible for anyone to be completely clear of the risk of infection, there are things you can do to help lower the risk.

Keep good personal hygiene, and try to minimise your contact with germs. It’s also advisable to protect your skin from scratches and cuts, for example, by wearing gloves when gardening. If you cut or graze yourself, wash your hands and then use tap water to clean the wound.

Spending time with friends and family can help your emotional wellbeing. However, if you have neutropenia, avoid being around people who are unwell with infections (for example a cold, flu, diarrhoea or chickenpox).

You should also follow food safety guidance for storing, preparing and cooking food. Check for a high food hygiene rating if you are eating out or buying food from places like food vans or stalls.

What side effects might I have?

Although the aim is to kill lymphoma cells, many types of chemotherapy also temporarily affect healthy cells. This is why chemotherapy can cause side effects.

Your medical team should advise you on whether they expect you to have side effects during or soon after your treatment. They should give you information about how to manage these.

Side effects can differ from person to person, even with the same treatment. Side effects also depend on the effects on your blood counts – anaemia (low red blood cells), neutropenia (low neutrophils, a type of white blood cell) and thrombocytopenia (low platelets).

Areas of your body that are most likely to be affected by chemotherapy are those where new cells are frequently made and replaced. For this reason, some of the more common side effects of chemotherapy include:

- Effects on your blood counts – anaemia (low red blood cells), neutropenia (low neutrophils, a type of white blood cell) and thrombocytopenia (low platelets).

- Hair loss – which could be thinning, partial or full loss, both on your head and other areas of your body.

- Digestive problems – such as feeling sick (nausea) and/or being sick (vomiting), and bowel problems, such as diarrhoea, constipation and wind (flatulence).

- Sore mouth (oral mucositis), where the lining of your mouth becomes swollen and painful.

Many people also experience extreme tiredness (fatigue) and cancer-related cognitive impairment (chemo brain), which affects thinking processes such as memory and attention.

You might be interested in our useful organisations listing, which includes a section on coping with the effects of cancer.

Tumour lysis syndrome

A rare but potentially serious side effect of chemotherapy is tumour lysis syndrome (TLS.) This can happen when chemotherapy kills a lot of cancer cells quickly. The contents of them are released into the bloodstream and can cause problems with your kidneys and heart.

If you are at risk of developing tumour lysis syndrome, your medical team will prescribe medicines to help prevent it.

What late effects might I have?

Your medical team should also talk to you about any possible late effects you might get. These are health problems that first appear months or years after treatment has finished.

The late effects you might get depend on which chemotherapy drug you have, the strength of the dose and how long your treatment goes on for. Your doctor should talk to you about possible late effects before you begin treatment.

Not everyone gets late effects, but it’s important to know what signs to look out for and to go for any follow-up appointments you’re invited to, to help keep a check on these.

Follow-up after chemotherapy

After finishing your treatment for lymphoma, you have regular follow-up appointments at the hospital. These involve conversations and physical tests with a member of your medical team.

One of the tests you are likely to have in the first few months after chemotherapy is your full blood count (FBC). This gives information about the numbers and sizes of your blood cells and tells doctors how well your bone marrow (where blood cells are made) is working.

The aim of follow-up is to:

- check your recovery after treatment

- check for signs of the lymphoma coming back (relapse)

- manage any late effects of treatment.

How often you are followed-up depends on a number of factors. These include the type of lymphoma you had, how long it’s been since you had treatment and whether you were treated as part of a clinical trial.

Chemotherapy webinar recordings

In addition to our animation explaining what chemotherapy is, we have some webinar recordings you might be interested in. Each of these feature health professionals and people affected by lymphoma.

- What is it like to have chemotherapy? (57 mins, 49 seconds)

- Recovering from chemotherapy (1 hour, 56 seconds).

Frequently asked questions about chemotherapy

Below, we give brief answers to some frequently asked questions about chemotherapy. Your medical team are best-placed to advise about your individual situation. Don’t hesitate to ask questions or for information to be repeated if this would help you.

Which chemotherapy drug or drugs will I have?

Most of the time, chemotherapy is given in a treatment plan that includes more than one drug (a combination regimen).

As well as your chemotherapy drugs, you might have other drugs as part of a chemotherapy regimen, for example:

- steroids, often as prednisolone tablets

- targeted therapies such as antibody therapies (for example rituximab); some of these are in tablet form. Others are given by injection, either into a vein (intravenous injection) or into a layer of fat under the skin (subcutaneous injection).

Your team might also recommend radiotherapy treatment as well as chemotherapy.

You might also have other treatments to help you with the side effects of chemotherapy, for example:

- G-CSF (granulocyte colony-stimulating factor), a growth factor given by subcutaneous injection. G-CSF helps you to make healthy new white blood cells. You might have this if you have a low number of a type of white blood cell called a neutrophil.

- Anti-sickness medicines (anti-emetics) to stop you from feeling and being sick. There are different kinds of anti-emetics. Tell your nurses or doctors if the one you’ve been given isn’t working, so that they can try another one.

How does my medical team decide which chemotherapy treatment to offer me?

Your medical team should discuss your treatment plan with you before you begin chemotherapy. The exact chemotherapy treatment your doctors recommend for you depends on a number of factors. These include the type of your lymphoma and, if applicable, its stage (a number that indicates which areas of your body are affected).

Your treatment plan should outline:

- the type of chemotherapy drug or drugs you’ll have

- how many treatment sessions you'll have

- how often you'll have treatment – after each treatment you'll have a break before the next session, to allow your body to recover.

Cancer Research UK has information about chemotherapy drugs used to treat non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) and chemotherapy drugs used to treat Hodgkin lymphoma.

Will I feel unwell during chemotherapy?

Many people feel unwell at some point during or after treatment. You might feel more unwell with additional cycles of chemotherapy.

Your medical team should talk to you about any possible side effects before you begin treatment, including when you might experience them.

If there’s something you would particularly like to feel as well as possible for (such as a family occasion), talk to them about this. They might be able to plan your treatment schedule around it.

Will I lose my hair?

Some types of chemotherapy can cause changes to your hair. These can include slight thinning, partial loss, complete loss and changes in colour or texture of your hair on your head as well as elsewhere on your body. Any effects on your hair are usually temporary. Your medical team can give you an idea of what to expect. We also have separate information about hair loss that you might be interested in.

Why is surgery unlikely to cure my lymphoma?

Surgery can only very rarely remove all the cancerous cells in lymphoma. Even for lymphomas that appear to be in one area only, surgery usually leaves some cells behind. It’s therefore not usually chosen to treat lymphoma.

How long do chemotherapy drugs stay in your body?

The length of time a drug stays in your body depends on factors such as the type of drug you have and how your body breaks it down. It can also depend on how well organs such as your kidneys and liver are working.

In most cases, drugs last a few hours to a few days in the body. It can, however, take longer for them to go completely out of your system. Ask your medical team about any precautions you should take during this time.

Is it safe to drink alcohol?

Generally, it should be OK to have the occasional alcoholic drink between chemotherapy cycles when you feel well enough, but check with your hospital consultant whether it is safe for you. Alcohol can interact with some drugs and affect how well they work. Remember, too, that you might feel the effects of alcohol more quickly now than you did before you had treatment.

Is it OK to smoke?

Smoking means that you are more likely to get infections, especially in the lungs. Some drugs used to treat lymphoma can also affect your lungs, including the chemotherapy drug bleomycin and the targeted drug brentuximab vedotin.

If you smoke, stopping can help to lower these risks. You can find information and advice to help you quit smoking on the NHS website.

Should I take exercise?

Physical activity can have a positive impact on physical and mental health. It could also help you to prepare for treatment, and in your recovery after treatment.

Speak to your doctor about the type and intensity of exercise that’s safe for you. You might be given certain safety precautions to follow, including avoiding certain types of exercise at times. For example, you’ll probably be advised against contact sports like rugby if you have a low platelet count (thrombocytopenia), due to the risk of bruising and bleeding. You might also be advised against swimming for a while because of the increased risk of infection from public pools and changing rooms.

Can complementary therapies help me?

There are many different types of complementary therapy that can be used alongside treatment for lymphoma (rather than instead of it). People often use complementary therapies to help with side effects and to increase their overall sense of wellbeing. Examples of types of complementary therapies we’re often asked about include massage and acupuncture.

Massage

Some people with lymphoma worry that having a massage could spread lymphoma throughout their body. There is no evidence that massages are at all harmful. Speak to your medical team for advice specific to your situation if you would like to have a massage.

Acupuncture

There is some evidence that acupuncture can help with feeling sick and being sick (nausea and vomiting) as side effects of chemotherapy. It could also help to relieve pain.

Speak to a member of your medical team if you think you’d like to try acupuncture, even if you have had it before. They might advise that you avoid it in certain cases, for example if you:

- are at risk of low platelets (thrombocytopenia), which could increase your risk of bleeding

- have low neutrophils (neutropenia), which could increase your risk of infection.

Should I follow a certain diet?

If you are having an intensive chemotherapy regimen, your medical team might give you advice on foods to avoid. However, the general guidance for people with lymphoma is the same as for people who do not have lymphoma, which is to eat a healthy, balanced diet.

Can I continue working or studying during treatment?

You are likely to need to take some time out of work during and after treatment for lymphoma.

Your employer must, by law, make reasonable adjustments that allow you to continue working during and after treatment (under the Equality Act 2010). Speak to your Human Resources (HR) department or your line-manager and ask how they can support you.

Where can I find out about day-to-day living during treatment for lymphoma?

We have more information about day-to-day living, including about working, studying and finances. You can also contact our Helpline team if you would like to talk about any aspect of lymphoma, including about practical concerns and emotional wellbeing.

Can I have a flu vaccination?

Ask your medical team whether they advise that you have the flu vaccination and when to have it.

- The vaccine might not work effectively while you are having chemotherapy. You might therefore be advised to have it either before or after finishing your course of chemotherapy.

- After finishing treatment with chemotherapy, it is sensible to have the flu vaccination each year.

Cancer Research UK has more information about flu vaccines and cancer treatment.

Find out more about vaccinations and lymphoma on our website.

Can I have sex?

Generally, sex and intimacy during treatment is considered to be safe. Check with your medical team about any precautions you should take, especially if you have low platelets (thrombocytopenia) as this heightens your risk of bruising and bleeding.

During chemotherapy treatment:

- Use a condom to avoid passing chemotherapy to your partner and to protect against infection. It is also generally not advisable to begin a pregnancy while you’re having chemotherapy or soon afterwards.

- The ‘pill’ (oral contraceptive tablets) might be less effective – talk to your GP or clinical nurse specialist about contraception if you are using the pill.

Some types of chemotherapy can cause difficulty getting or keeping an erection (‘impotence’ or ‘erectile dysfunction’) in men. In women, they can cause vaginal dryness. Talk to a member of your medical team for help if you’re affected by these issues.

How long should I wait after treatment before getting pregnant?

It’s generally not a good idea to begin a pregnancy while you are having chemotherapy or soon afterwards. Your medical team can give you advice specific to your individual situation. In general, women are advised to wait for two years after finishing treatment before trying for a baby. Men are usually advised against getting their partner pregnant during, and for at least six months after, finishing chemotherapy.

Your medical team will talk to you if your chemotherapy could affect your fertility before you begin treatment.

Can I breastfeed while I am having treatment?

Doctors usually recommend that you do not breastfeed your baby while you’re having chemotherapy. This is because the drugs can get into your breast milk. Ask your medical team for advice specific to your situation about the safety and practicalities of breastfeeding.

Can I go on holiday when I am having chemotherapy?

Most doctors would not recommend travelling outside of the UK during chemotherapy and for a few months afterwards. Short breaks in the UK are usually fine so long as you feel well enough and can get to a hospital quickly if you need medical attention.

Discuss the safety of your travel plans with your medical team before you travel and make sure that you have suitable travel insurance in place before you go.