Splenectomy

Some people with lymphoma need to have an operation to remove the spleen. This is called a splenectomy. Without a spleen, it's harder for your body to fight infections, so you need to take precautions to lower your risk of getting them.

On this page

How can lymphoma affect the spleen?

Symptoms of an enlarged (swollen) spleen

What is the spleen?

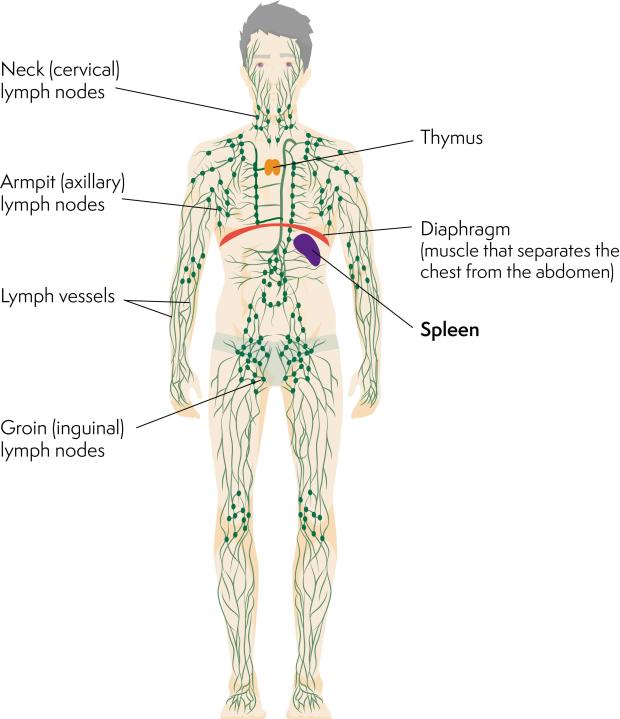

The spleen is part of your lymphatic system, which helps to protect your body against infection.

The spleen is positioned behind your ribcage on the left side of your body, just behind your stomach. It lies below your diaphragm (sheet of muscle separating your chest from your tummy). A spleen is soft and purple. Doctors can sometimes feel it from the outside of your body.

What does the spleen do?

The spleen helps to protect you from infection. It does this by:

- filtering bacteria and viruses from your bloodstream

- making white blood cells and antibodies.

Other jobs the spleen has to do are to:

- filter your blood to remove red blood cells (which carry oxygen around your body) and platelets (which reduce bruising and bleeding) that are old and/or damaged

- store a small supply of red blood cells and platelets for your body to use in an emergency

- make new blood cells if your bone marrow (which usually makes blood cells) isn’t working as it should.

How can lymphoma affect your spleen?

There are different ways that lymphoma can affect your spleen.

Swollen (enlarged) spleen

If lymphoma cells build up inside your spleen, it makes it swell (enlarge). This is known as ‘splenomegaly’ and can happen in different types of lymphoma.

If your spleen is enlarged, more red blood cells and platelets than usual fit inside it. They are filtered too quickly from the bloodstream, leading to a lower number of these types of cells in your bloodstream. This can cause anaemia (low red blood cell count) and/or thrombocytopenia (low platelet count).

My doctor thought I had an enlarged spleen, so it was suggested I have blood tests straightaway. Within a day I received a phone call from a consultant haematologist asking me to go and see him. Instead of being tucked under my ribs on the left side, my spleen stretched right across my tummy (abdomen). This, along with the night sweats I was experiencing and the loss of weight flagged a serious problem to the haematologist. After further tests, I was diagnosed with low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Spleen working harder than it should

Lymphoma can make your spleen work harder than usual, which can lead to it swelling. For example, if your lymphoma:

- causes autoimmune haemolytic anaemia, your spleen has to work harder to remove antibody-coated red blood cells.

- is in your bone marrow, your spleen might work harder to take on the bone marrow’s usual role of producing new red blood cells.

Symptoms of an enlarged (swollen) spleen

Sometimes, an enlarged spleen doesn’t cause any symptoms. However, you might experience:

- pain in the top left side of your tummy, behind your ribs

- feeling full soon after eating

- anaemia, which can make you feel very tired

- feeling short of breath, particularly when doing physical activity

- getting more infections than usual

- bleeding or bruising more easily than usual.

Tell your doctor if you experience any of these symptoms. Doctors can sometimes tell whether your spleen is enlarged by feeling your tummy. However, you might be referred for a blood test, CT scan or MRI scan to know for certain.

Why might I need my spleen removed (splenectomy)?

If you have lymphoma, you might need to have your spleen removed in the following instances:

- To look at your spleen in the laboratory, so that doctors can work out which type of lymphoma you have, or to see whether lymphoma is in your spleen.

- If you have anaemia or thrombocytopenia, for which other treatments haven’t worked well. Removing the spleen can help to improve the red cell count and/or the platelet count, because the spleen will no longer be sorting blood cells and removing them from your bloodstream.

- As part of treatment for lymphoma (for example, in some cases of splenic marginal zone lymphoma).

Having a splenectomy

A splenectomy operation is carried out under general anaesthetic. Mostly, it’s done as keyhole (laparoscopic) surgery, but it can also be done as open surgery. Your consultant will talk to you about what the surgery involves. They will explain why it might be a suitable treatment option for you, and the benefits and risks of possible complications.

The Royal College of Surgeons of England has information about different types of surgery.

Before a splenectomy

Before you have a splenectomy, you have some tests to check that you are well enough to have the operation. Unless it’s being done as an emergency, you are usually recommended to have some vaccinations in the weeks before a splenectomy. The anaesthetist talks to you about your anaesthetic and the pain relief you might have afterwards. which your surgeon will discuss with you before your operation.

Tests to check that you are well enough to have the operation

Before your operation, you have:

- Blood tests to check blood cell counts. Your blood group is also checked, in case a transfusion is needed. Sometimes, blood tests are also used before an operation to check blood clotting, kidney and liver functioning.

- An electrocardiogram (ECG), which records the rhythm and electrical activity of your heart.

These tests are to make sure you are well enough to have surgery.

You might also be referred to a high-risk anaesthetic clinic in preparation for surgery, especially if you have some other medical problems that need to be taken into consideration.

Vaccinations before a splenectomy operation

If your splenectomy is a planned (not emergency) operation you are usually recommended to have some vaccinations in the weeks leading up to it. This is to lower your risk of becoming unwell due to infections afterwards.

The vaccinations you might be asked to have include those to help protect against meningitis, influenza (flu), pneumonia, measles, mumps and rubella and chickenpox.

Laparoscopic (keyhole) surgery

Laparoscopy is a type of surgery that uses a mini camera (laparoscope) to see inside your tummy (abdomen) without making a large cut (incision). It takes longer than open surgery, but recovery is often quicker.

- Your surgeon makes a few small incisions in your tummy. Usually, these are no more than 1.5cm (half an inch) in length.

- They put a laparoscope into one of the incisions so that they can see inside your tummy.

- The images from the laparoscope are magnified and sent to a TV screen to help guide your surgeon.

- Your surgeon also pumps gas into your tummy to make it easier to operate, which they let out after surgery.

- They use the other incisions to put tools in to remove your spleen.

- You might have a thin plastic tube (drain) coming out of your left side to drain away any blood or fluid.

- At the end of surgery, your surgeon stiches up all incisions and covers them with dressings. The stitches are dissolvable so you don’t need to have them taken out.

Sometimes, you can go home later the same day, but usually you stay in hospital at least overnight to check your recovery from surgery.

Laparoscopic surgery takes a bit longer than open surgery but it generally causes less bleeding and pain. You usually recover faster and can go home sooner than with open surgery.

Occasionally, laparoscopic surgery isn’t possible – for example, if your spleen is too large or bleeds too much. Although open surgery might be planned, there is a possibility that your surgeon might need to switch to open surgery during the operation. They will discuss this possibility with you before your surgery.

I felt very nervous about having keyhole surgery, but I was assured that recovery would be very quick. I was also told that I’d be in partial remission from my lymphoma afterwards, so it was sensible to go ahead. I actually ended up feeling quite positive about it. Although keyhole had been planned for me, my surgeon ended up having to do my splenectomy as open surgery. My recovery was quite quick and I was back to work in 6 weeks.

Open surgery

With open surgery, your surgeon makes a cut (incision) to see directly into your body in order to remove your spleen.

- While you are under general anaesthetic, your surgeon makes an incision. Usually, this is underneath the bottom of your ribcage on the left, or straight down the middle of your tummy (abdomen).

- At the end of the operation, the cut is stitched up and covered with a dressing.

- When you wake up, you might have a thin plastic tube (drain) coming out of your left side to drain away any blood or fluid. You might also have a thin plastic tube coming out of your bladder (catheter) to drain your wee (urine), and a small plastic tube (drip) going into your arm.

You have to stay in hospital for a few days to recover. Depending on how your incision is closed, you might have your surgical staples (skin clips) or stitches removed after a week or two.

After your operation

Most people feel some pain or discomfort after a splenectomy. Your doctor will prescribe pain relief medication. You might be given it in tablet form, into a drip in your arm, through a small plastic tube next to the wound, or through a small plastic tube in your back – this depends on factors that include the type of surgery you had (laparoscopic or open). If you still feel pain after taking pain relief medication, tell a member of your medical team. They might prescribe a different type of pain relief or a higher dose.

You should be able to eat and drink as normal soon after the operation. You start off with fluids once you recover from a general anaesthetic, and build up slowly to eating solids later that day or the next morning.

In complex cases, you might have to fast (not have anything to eat or drink, except water) and have a small tube inserted through your nose to empty your stomach. Such cases, however, are rare. An example would be if your spleen is very large and has become stuck to your stomach.

Your surgeon will give guidance on how to look after yourself at home. If you go home on the day of your operation, someone should stay with you for at least the first 24 hours after the operation. This is so that they can look after you and help with any necessary tasks while you rest. Tell your surgeon if you do not have someone to offer such support so that they can arrange for you to stay in hospital.

Wound healing is a gradual process. Dressing are usually kept on for 5 days, in order to keep the area dry. You will have a scar where any incisions are made. These will gradually fade.

Recovery

For most people, recovery usually takes a few weeks. Generally, doctors recommend that you move around as soon as possible after your operation. Most people are back to many of their normal activities within a week.

- If you work, you might be encouraged to take 2 weeks off after your operation. Depending on what you do, you might be encouraged to build back up to your full range of duties over 4 to 6 weeks.

- If you drive, let your insurers know about your operation. Many companies ask that you do not drive for 2 weeks after a splenectomy operation.

Talk to your surgeon or nurse about when you can expect to get back to your day-to-day activities, exercise, and driving.

Potential complications of splenectomy

As with any surgery, splenectomy comes with risks of complications. These include risks related to:

- Having an anaesthetic – your surgeon can talk to you about your individual risks of these. The NHS website also has information about the general potential risks and complications of anaesthetic.

- Not moving around as much as usual in the days after an operation, particularly if you are in pain or if you had a drain or catheter.

The potential complications of splenectomy include internal bleeding, chest infection, wound infection and blood clots. These are all uncommon.

Your surgical team take care to lower these risks during surgery. They also keep checks on you during your recovery so that they can spot any potential signs of complications and take action early if they need to.

If you notice any redness, swelling or oozing around your wound(s), or if you develop a temperature of 38°C or above, contact your GP or hospital straightaway. You might need antibiotics.

More serious complications of splenectomy are very rare. They include a severe reaction to anaesthetic, or damage to another organ or major blood vessel during the operation.

Your surgeon will discuss any longer-term risks with you. These relate to the spleen no longer being there to help prevent infection.

Precautions to take after a splenectomy

Without a spleen, your immune system won’t work as well as it used to. Your liver, bone marrow and lymph nodes take over many of the jobs your spleen used to do. However, some infections could develop quickly and become severe. You are also more vulnerable to infections such as pneumonia and meningitis, and a rare, but potentially serious infection called overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI).

To help protect yourself from infection:

- Lower your risk of cuts and scratches – for example, wear gloves for gardening. Seek medical advice straightaway if you have an injury, including if an animal bites or scratches you. You might also be interested in our information on preventing infection, which gives more tips on how to protect yourself from infection.

- Carry a splenectomy card – this is to tell people in the case of a medical emergency that you don’t have a spleen. These are available for free on the UK government website, or you might prefer to buy a piece of medical jewellery or accessory with this information on.

- Have the annual Influenza (flu) vaccination and any other vaccinations your medical team recommend.

To help reduce the risk of getting a chest infection or blood clot, you might be given breathing and leg exercises to do at home. You might also have blood-thinning injections for a week or more after your operation. Your surgeon or anaesthetist will talk to you about this on the day of your surgery and will teach you how to inject yourself.

If you’ve had chemotherapy, your risk of infection is higher after a splenectomy that it would otherwise be. This is because both chemotherapy and the lymphoma itself affect your immune system.

Be aware of the symptoms and signs of infection, including of overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI) – contact a member of your medial team straightaway if you notice any, in case you need treatment. Although it is impossible for anyone to be completely risk-free, it is a good idea to take precautions to help lower your risk of developing an infection.

Watch this video of Jackie talking about her experience of having a splenectomy.

Overwhelming post-splenectomy infection (OPSI)

If you don’t have a spleen, there is a small but serious risk of developing ‘overwhelming post-splenectomy infection’ (OPSI). This can be a life-threatening infection. The risk of OPSI is highest in the first 2 years after your surgery but it never goes away completely.

Symptoms of OPSI include:

- fever (a body temperature above 38°C or 100.4°F)

- chills

- muscle aches and pains

- headache

- vomiting

- tummy pain.

Antibiotics

After a splenectomy, you usually need to take low-dose antibiotics each day, at least for the first 2 years after the operation and often for the rest of your life. This is to help prevent you from developing infections. You might also be given a course of extra or ‘spare’ antibiotics to keep at home, in case you need them quickly. Your doctor will give you information about this. If you have any questions about your antibiotics, contact your GP or your hospital for advice.

I have to take two penicillin antibiotic tablets every day for the rest of my life. I don’t seem to get many infections, maybe because people are careful and don’t come and see me if they’ve got a cold or any infections.

Travelling to another country

If you are planning a trip to another country, talk to your doctor about the risks and about any travel vaccinations you might need. Have this conversation well ahead of going, to allow enough time for any vaccinations that need to be given several weeks before you travel.

Without a spleen, you are also at a higher risk than you otherwise would be of getting malaria (a very serious tropical disease spread by some mosquitoes). Ask your doctor about anti-malaria tablets, which are most suitable for you, and how best to protect yourself against mosquito bites.