Lymphoma in children

This information is about lymphoma in children under 15. It is aimed at parents and carers of children who have lymphoma. It might also be helpful for other adults who are looking after a child with lymphoma. We say ‘your child’ to mean any child with lymphoma, even if you are not their parent, guardian or primary caregiver.

We have separate information for young people (up to 24 years old) with lymphoma. This is aimed at young people themselves, but it might also be useful for parents and carers of this age group. We also have separate information on practicalities when a child has lymphoma.

There is a lot of information on this page. You might want to read it in chunks. You can use the links under ‘On this page’ to help you navigate to the parts that are most relevant to you.

On this page

We have a storybook, Tom has lymphoma, specially written and illustrated for children of primary school age. It is designed for you to read with your child to help them understand what lymphoma is and the treatment it involves. We also produce information in Easy Read format, which uses simple words and illustrations to explain about lymphoma. You might also find it helpful to download our book for carers: When someone close to you has lymphoma.

We produce a separate Young person’s guide to lymphoma, which is designed for teens and young adults affected by lymphoma.

You can download these books or order a printed copy free of charge.

What is lymphoma?

Lymphoma is a type of cancer. It develops when white blood cells called lymphocytes grow in an uncontrolled way.

Lymphoma is the third most common cancer in children – but it is still rare. Every year in the UK, around 160 children under 15 are diagnosed with lymphoma. Around 2 in 3 of these are boys and 1 in 3 are girls.

If your child has lymphoma, it’s not because of anything you – or they – did or did not do. They can’t catch lymphoma and they can’t give it to anybody else. In most cases, the cause of lymphoma is not known.

Hear Laura share her experience of her 5 year old son having lymphoma.

Types of lymphoma in children

There are lots of types of lymphoma. They are split into two main groups:

Hodgkin lymphoma

Around half of children diagnosed with lymphoma have Hodgkin lymphoma.

- Most have a type called classical Hodgkin lymphoma.

- About 1 in 5 have a less common type called nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL).

Non-Hodgkin lymphoma

Around half of children diagnosed with lymphoma have non-Hodgkin lymphoma. There are lots of different types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Different types are often grouped together depending on how they behave. Some types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma grow slowly (low-grade lymphomas) and others grow more quickly (high-grade lymphomas). Most non-Hodgkin lymphomas in children are high-grade. Although this might sound alarming, high-grade lymphomas generally respond very well to treatment and are very likely to go into remission (no evidence of lymphoma) with the right treatment.

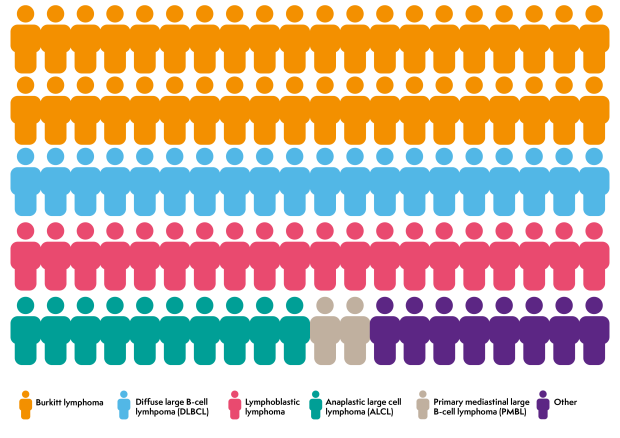

The most common types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children are:

- Burkitt lymphoma, accounting for around 40 in every 100 cases of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), accounting for 10 to 20 in every 100 cases of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- lymphoblastic lymphoma, accounting for around 20 in every 100 cases of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- anaplastic large cell lymphoma (ALCL), accounting for around 10 in every 100 cases of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma

- primary mediastinal large B-cell lymphoma (PMBL), accounting for 1 to 2 in every 100 cases of childhood non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Other types of non-Hodgkin lymphoma are very rare in children.

Symptoms

Many of the symptoms of lymphoma can also be symptoms of other illnesses. This can make lymphoma difficult to diagnose.

The symptoms your child might experience depend on where the lymphoma is in their body. Symptoms vary from child-to-child even if they have the same type of lymphoma.

On this page, we cover the most common symptoms of lymphoma in children:

- swollen lymph nodes

- tummy symptoms

- chest symptoms

- general symptoms

- low blood counts

- brain and nerve symptoms.

Your child might have some of these symptoms but not others, or they might have different symptoms.

Having any of these symptoms does not necessarily mean your child has lymphoma. They are often caused by other, less serious illnesses. If you are worried about your child’s symptoms, contact your GP.

Swollen lymph nodes

The most common symptom that children or their parents or carers notice is a lump or lumps that don’t go away after a few weeks. These lumps are swollen lymph nodes. Lymph nodes often swell when children have an infection, such as a cold, an ear infection or a sore throat. Swollen lymph nodes caused by infections are usually painful to the touch and go down within 2 or 3 weeks. Swollen lymph nodes caused by lymphoma aren’t usually painful and don’t shrink back down. In children, they might grow quickly.

Swollen lymph nodes often develop in the neck, armpit or groin. You will probably be able to feel these lumps. Some might develop deeper inside your child’s body, such as their tummy or chest, where you can’t feel them. These cause different symptoms depending on where they are.

Tummy symptoms

If your child has lymphoma in their tummy (abdomen), they might get tummy pain, sickness, diarrhoea, constipation or a swollen tummy.

Chest symptoms

If your child has lymphoma in their chest, they might wheeze or get out of breath easily, or develop a cough that doesn’t go away. Occasionally, the lymphoma presses on blood vessels in the chest. If this happens, your child might get a red, swollen face and the veins in their neck might look more obvious than usual.

General symptoms

Lymphoma can cause general symptoms due to the way your child’s body reacts to the lymphoma cells. These include:

- fatigue (extreme tiredness that doesn’t get better with rest)

- drenching sweats, especially at night – these can be so severe that you need to change your child’s nightclothes and bedding

- a high temperature (above 38°C or 100.4°F) that might come and go

- a poor appetite

- losing weight without trying to

- itching.

Night sweats, weight loss and a high temperature (fever) often occur together. They are sometimes called B symptoms. Your child’s doctor will consider whether or not your child has B symptoms when they decide on the most appropriate treatment for them.

Low blood counts

If your child has lymphoma in their bone marrow (the spongy part of bones where blood cells develop), they might get low blood counts. This will show up on blood tests, but it can also cause symptoms such as:

- tiredness

- shortness of breath

- bruising or bleeding more easily than usual

- picking up infections easily that last longer than usual.

Brain and nerve symptoms

Rarely, lymphoma can affect the nerves or brain. This might cause symptoms such as headaches, dizziness or fits (seizures).

Tests

If your child’s GP thinks your child might have lymphoma, they will refer them urgently to be assessed by a specialist. Your child will need tests to find out for certain.

To confirm a diagnosis of lymphoma, your child will need to have a small operation called a biopsy. This involves removing a lymph node, or taking a sample of cells from one, for testing. Depending on how old your child is and where the lymph node is, they might have their biopsy under:

- a local anaesthetic, which numbs the area where the sample is being taken so they don’t feel anything

- a general anaesthetic, which means they are asleep for the whole procedure.

Some lymph nodes are near the surface of the skin, where it is easy to take a biopsy. If your child has lymph nodes that are deeper inside their body, they might have an X-ray or scan to help their doctor find the best place to take the biopsy. They usually take the biopsy sample using keyhole surgery – your child is very unlikely to need open surgery even if the affected lymph nodes are deep inside their chest or tummy.

I had never had an anaesthetic before so I was a bit nervous, but the nurses and doctors were really kind and cheerful when they told me what was going to happen. When they put in the anaesthetic I had no time to really worry about anything because I was fast asleep in an instant.

An expert lymphoma pathologist looks at the biopsy sample under a microscope to find out whether or not it is lymphoma. If it is, they will carry out more lab tests on the sample to find out exactly what type of lymphoma it is.

Staging

If your child has lymphoma, they need more tests to find out how much lymphoma they have in their body and exactly where it is. This is called staging. Knowing the stage of your child’s lymphoma helps their specialist plan the best possible treatment for them.

The tests might include:

- blood tests to find out how lymphoma is affecting your child and to check their general health

- scans such as a PET/CT scan, MRI scan, ultrasound scan or X-ray to see where the lymphoma is in your child’s body

- a bone marrow biopsy to check for lymphoma in the bone marrow (although this can often be seen on a PET/CT scan instead)

- a lumbar puncture if your child’s specialist thinks they might have lymphoma affecting their brain or nerves.

Your child does not necessarily need all of these tests – their doctor orders the most appropriate tests depending on the type of lymphoma your child has and how it is affecting them.

Your child’s specialist uses the results of all these tests to work out the stage of your child’s lymphoma. In children, Hodgkin lymphoma and non-Hodgkin lymphoma are staged differently. Both systems work out if your child’s lymphoma is ‘early stage’ or ‘advanced stage’. Your child’s medical team might tell you their stage as a number. Stages are numbered from 1 to 4. Stage 1 and 2 are early stage. Stage 3 and 4 are advanced stage.

Because lymphocytes travel all over the body, lymphoma is often advanced stage by the time it is diagnosed. This might sound alarming, but advanced stage lymphoma can be treated very successfully and most children have a good outlook.

Outlook

Your child’s lymphoma specialist is the best person to talk to about your child’s outlook, because they know all of your child’s individual circumstances.

In general, though, treatments for children with lymphoma are very successful. Most children who have lymphoma go into complete remission and stay in remission. Complete remission means that tests and scans at the end of treatment show no evidence of lymphoma left in the body.

Cancer Research UK has information on children’s cancer statistics if you would like to learn more. If you choose to look at survival statistics, remember that they can be confusing. They don’t tell you what your child’s individual outlook is – they only tell you how a group of people with the same diagnosis did over a period of time. Treatments are improving all the time and survival statistics are usually measured over 5 or 10 years after treatment. This means that statistics only tell you how people did in the past. Those people may not have received the same treatment that your child will receive. A lot of statistics are very general and include people of all ages. Cure rates in children are much higher than in older people so the information you find might not be relevant for your child.

Your medical team will share with you the most relevant statistics related to the diagnosis your child has.

Treatment

Different types of lymphoma need different treatment. Your child’s specialist will work with a team of health professionals (a ‘multidisciplinary team’) to decide on the best option for your child. They consider the type of lymphoma your child has and how it is affecting them, as well as other factors such as your child’s age and general health.

Treatment decisions are made individually for each child. Your child’s specialist is the best person to talk to about the exact treatment they recommend for your child. However, in general:

- Your child is likely to be offered treatment as part of a clinical trial, if there is one suitable for them.

- Most children have chemotherapy. This might be combined with antibody therapy.

- Some children have radiotherapy.

- Surgery is rarely used for children with lymphoma, except for children with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL).

There is more about different types of treatment in the sections below.

Most children are treated at specialist hospitals that have all the facilities they need to diagnose and treat children with cancer.

Clinical trials

Your child’s specialist might suggest that your child is treated as part of a clinical trial, if there is one suitable for them. Clinical trials are medical research studies involving people. Many children with cancer take part in clinical trials so that scientists can find better ways to treat them. They aim to find out if new treatments, or new ways of using existing treatments, are better than current treatment options. Treatment for lymphoma in children is generally very successful, so the focus of many trials is to limit side effects, especially in the long-term, while still giving every chance of sending the lymphoma into remission.

If you’re interested in hearing about clinical trials that might be suitable for your child, ask your child’s specialist.

Clinical trials are voluntary. If you don’t want your child to take part, they don’t have to. If your child is in a trial but you don’t want to continue with it, you can opt out at any time. In this case, your child’s specialist will give your child the best standard treatment instead.

You can find out more about clinical trials, or search for a trial that might be right for your child, in our dedicated section, Lymphoma TrialsLink.

Chemotherapy

Chemotherapy means treatment with drugs. Chemotherapy to treat cancer uses drugs that kill cells. Cancer cells usually divide and grow more rapidly than most healthy cells. Chemotherapy works by killing cells that are actively dividing – which is why it is effective at killing cancer cells. However, it can also kill healthy cells that divide rapidly, such as hair root cells, skin cells and blood cells. This is what causes some of the side effects of chemotherapy.

Lots of different chemotherapy drugs are used to treat lymphoma. Usually, several drugs that kill cells in different ways are given together, to kill as many lymphoma cells as possible. Each combination of drugs is known as a chemotherapy regimen. Chemotherapy regimens often have complicated names, such as OEPA, COPDAC or ABVD. These are usually abbreviations of the names of drugs they include.

Watch our chemotherapy animation to find out how chemotherapy works and why it is given in cycles

What chemotherapy will my child have?

Lots of different chemotherapy regimens are used to treat lymphoma in children. Your child’s multidisciplinary team will recommend a chemotherapy regimen based on your child’s individual circumstances. Their specialist will explain which treatment they are recommending, and why they think it is the best choice for your child. They will give you information about what to expect and what side effects your child might experience.

How long will chemotherapy take?

Chemotherapy is given in cycles. A cycle is a block of chemotherapy followed by some time off treatment to let your child’s body recover. Most children with lymphoma have several cycles of chemotherapy over several months. They might stay in hospital for some of their treatment and have some as an outpatient. This is when your child goes into hospital for a few hours at a time to have treatment and comes home straight afterwards.

The number of cycles of chemotherapy your child needs depends on the type and stage of their lymphoma and the exact treatment they are having. Your child’s specialist will tell you how many cycles your child is likely to need and how long this will take.

- Children with Hodgkin lymphoma are likely to have a PET scan after their first few cycles of chemotherapy. The results of the scan are used to decide how many more cycles of chemotherapy your child needs, and if they need radiotherapy after finishing their chemotherapy.

- Treatment for non-Hodgkin lymphoma in children is sometimes given in phases, using different chemotherapy drugs at different times. Your child’s specialist will tell you what treatment your child needs at each phase and how long each phase is expected to take. Depending on the type and stage of your child’s lymphoma, their treatment might include:

- Cytoreductive therapy: a short period of treatment to reduce the number of lymphoma cells in their body. This helps prevent some of the side effects of intensive treatments.

- Remission induction: a period of intensive treatment to put the lymphoma into remission.

- Consolidation: a period of less intensive treatment to keep the lymphoma in remission.

- Reinduction: another period of intensive treatment to get rid of any lymphoma cells that might have been left behind.

- Maintenance: a period of gentler treatment to stop the lymphoma coming back.

How is chemotherapy given?

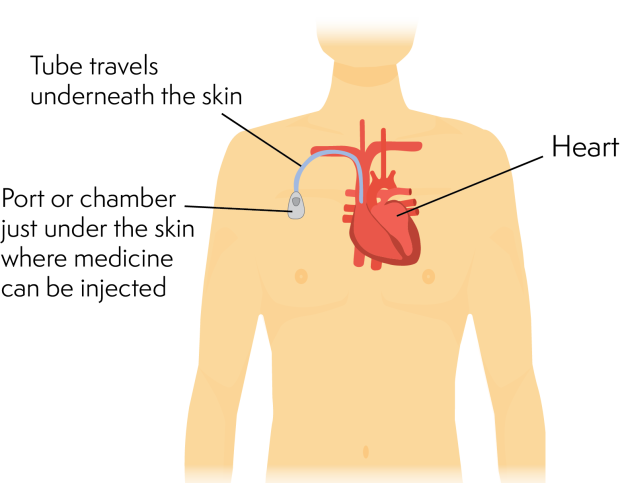

Many chemotherapy drugs are given through a drip into a vein (intravenously). Children usually have a line called a portacath put in to make this process easier. A portacath can also be used to take blood samples for blood tests.

A portacath is a thin, soft tube that goes underneath the skin and into one of the main veins just above the heart. It has a small chamber or port at the end, that sits just underneath your child’s skin. Medicines can be injected directly into the port.

A portacath is put in place under general anaesthetic. Once in place, it usually stays in for the whole of your child’s treatment. Your child’s medical team will tell you how to look after the line at home. It is taken out at the end of treatment.

Your child might have some drugs by mouth. This could be tablets, capsules, or syrup.

Some children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma might also need chemotherapy given directly into the fluid around the spinal cord. This is called intrathecal chemotherapy. It is given through a thin needle in the lower back (a lumbar puncture). Intrathecal chemotherapy helps stop lymphoma spreading to the brain or spinal cord. Not all children need intrathecal chemotherapy.

Your child is monitored closely throughout treatment. Their specialist checks how much lymphoma has been killed and how well your child is coping with the treatment.

Radiotherapy

Radiotherapy uses powerful X-rays to kill lymphoma cells. It is not often used to treat children with non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Some children with Hodgkin lymphoma might have radiotherapy if they have some lymphoma left in their body after their first two cycles of chemotherapy. In this case, it is given after they finish their chemotherapy.

Radiotherapy is given over several days or weeks, usually as an outpatient. Each treatment only lasts a few minutes. Even though the treatment time is short, your child’s appointment might take a while because they need to be positioned very carefully and keep very still. This makes sure the X-rays are focused precisely on areas affected by lymphoma to reduce the effect on healthy cells. The hospital might make a special mould to hold your child in the correct position.

The lowest possible dose of X-rays is used to reduce the risk of damaging growing bones and muscles or harming organs. It also lowers the chance of late effects (side effects that develop long after treatment has finished).

The type of radiotherapy used in lymphoma treatment doesn’t make your child radioactive. You can still be close to your child when they have had radiotherapy.

Targeted treatments and antibody therapies

Targeted treatments are medicines that have been specially designed to attack particular proteins or chemical signalling pathways in lymphoma cells. They attack lymphoma cells more precisely than chemotherapy. This means they are able to kill lymphoma cells with fewer unwanted effects on healthy cells. Most targeted treatments are not routinely available to treat children yet, but your child might be offered one as part of a clinical trial. They are sometimes given on their own, and sometimes in combination with chemotherapy.

Antibody therapy is a type of targeted treatment. It uses antibodies that have been specially made in a lab to stick to a protein on a cancer cell. This activates the immune system to destroy the cancer cell.

Rituximab is an antibody therapy that can be used to treat Burkitt lymphoma and DLBCL in children. It is given through a drip or central line, in combination with chemotherapy. Your child has pre-medication first, to help prevent any reactions. They have their first dose of rituximab very slowly, so their specialist can check for any reactions. They have rituximab in cycles, to fit in with their chemotherapy cycles. How often your child has rituximab varies depending on the particular chemotherapy they are having.

Surgery

Surgery is rarely used to treat lymphoma because in most cases, it isn’t possible to remove all the lymphoma cells. Children with nodular lymphocyte-predominant Hodgkin lymphoma (NLPHL) that is only affecting one lymph node might be able to have it surgically removed and might not need any other treatment. If your child has surgery for NLPHL, they will be closely monitored afterwards to check for any signs of lymphoma coming back.

Side effects of treatment

Treatment aims to kill lymphoma cells, but it can also damage some of your child’s healthy cells. This can cause unwanted effects on your child’s body, known as side effects.

Most side effects are short-term but some of them can be longer lasting.

Everyone responds differently to treatment, so it is difficult to predict exactly what side effects your child might get. Your child’s medical team will tell you about side effects that might happen with your child’s treatment, and will monitor your child carefully for them.

Side effects that commonly occur during treatment for lymphoma include:

- feeling sick or being sick

- hair loss

- low blood counts:

- a low level of neutrophils, a type of white blood cell that helps fight infections, increases the risk of getting infections

- a low level of red blood cells, which carry oxygen around your body, can cause tiredness or shortness of breath

- a low level of platelets, which help blood clot, can lead to easy bruising or bleeding for longer than usual after a minor injury

- sore mouth and throat

- weight loss or weight gain.

Some treatments for lymphoma might affect your child’s fertility in the future. Your child’s specialist should tell you if this is likely to be the case. If it is, they will talk to you and your child (if appropriate) about options you might wish to consider to help preserve their fertility.

Tell your child’s medical team if your child has any side effects, even if you haven’t seen them mentioned as side effects anywhere and however minor they seem. There are effective treatments for many side effects. Your child’s medical team can also advise you on things you can do to help your child cope.

What happens if lymphoma comes back or doesn’t respond to treatment?

Most children with lymphoma are treated successfully and stay in remission.

Occasionally, lymphoma comes back (relapses) after treatment, or may not respond to treatment as well as expected (refractory lymphoma). If your child has relapsed or refractory lymphoma, their specialist will suggest different treatment options.

Your child might be offered treatment as part of a clinical trial. This might include options used to treat adults with lymphoma that are not yet routinely available for children, such as:

- a targeted treatment such as pembrolizumab or nivolumab

- antibody therapy such as brentuximab vedotin or polatuzumab vedotin

- CAR T-cell therapy.

If there isn’t a clinical trial suitable for your child, or they don’t want to take part in one, other options include a different combination of chemotherapy drugs (sometimes given with radiotherapy) or high-dose chemotherapy followed by a stem cell transplant.

After treatment

Your child has tests and scans during and at the end of their treatment to check how well they have responded. If these tests and scans show no evidence of lymphoma, it is called remission. Once treatment is finished and your child is in remission, they have follow-up appointments at the clinic for many years. These are to check that:

- Your child is recovering well from treatment.

- They are growing and developing well.

- There are no signs of the lymphoma coming back. The risk of this happening gets much lower over time.

- Your child is not developing any late effects from their treatments (side effects that can develop months or years later).

Late effects of treatment

Most children who are treated for lymphoma recover well with few long-term effects. However, because they have had cancer treatment, they have a higher risk of developing certain health problems in later life than people who have not been treated for cancer. These are called late effects. They can develop months or years after treatment for lymphoma. They include:

- fertility problems

- effects on growth

- other cancers later in life

- heart disease

- lung problems

- hormone problems.

Your child’s specialist monitors them carefully for late effects at follow-up appointments. They should also tell you any signs to look out for. Detecting late effects early can limit the problems they cause.

Further information and support

If you would like more information or you want to talk about any aspect of your child’s lymphoma, please contact us. You can also call our Helpline on freephone 0808 808 5555, or use our live chat function. You might also find our page on practicalities when a child has lymphoma helpful. It addresses common practical concerns that parents and carers of children with lymphoma have.

Our resources on talking to children about lymphoma are designed to help parents and carers who have lymphoma talk to their children about it, but you might find some of the suggestions helpful. They include animations about Hodgkin and high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma, and low-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

There are also many other organisations that provide information and support for children with cancer, and their parents and carers.