Lymphoma drug development, approval and funding

This information outlines how new drugs are developed and approved, and who decides whether they can be prescribed on the NHS.

On this page

Drug development

There are lots of new drugs being developed to treat lymphoma but it is a long and expensive process. It can be frustrating hearing about new drugs that could improve outcomes for people with lymphoma when these are not yet available. However, it’s important that all new drugs are thoroughly tested to make sure they are safe and effective.

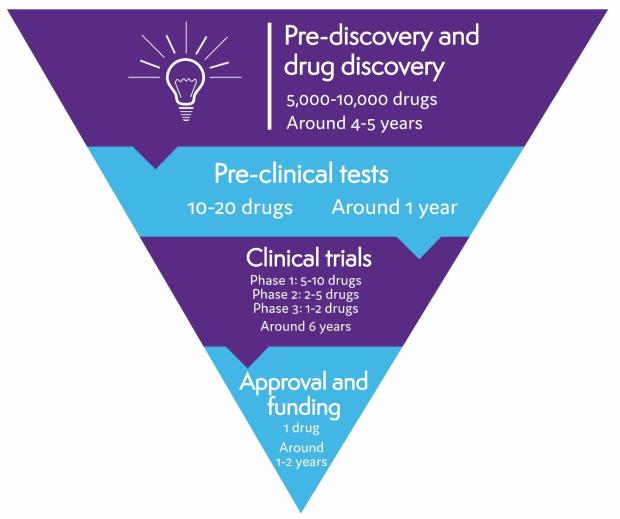

On average, it takes 10 to 15 years and costs more than £1 billion to develop a drug from discovery to approval. Thousands of drugs are tested in early research, but only a few pass all the checks needed to make sure they are safe and work well.

Pre-discovery and drug discovery

The first stage in drug development for lymphoma involves research to understand why lymphoma develops and what makes lymphoma cells different from healthy cells. This research helps identify possible targets for a drug to act on – for example, a particular protein found on the surface of lymphoma cells, or a protein that stops your immune system recognising and destroying lymphoma cells.

Scientists then design or search for drugs that act on the targets they’ve identified. Thousands of possible drugs are tested in this way but only a few are successful enough to get to the next stage of testing.

Pre-clinical tests

Before a drug can be tested in humans, it is tested thoroughly in laboratories, using computer modelling, and in animals. These tests help find out how the drug works, what effects it might have on the body, and what dose should be safe to start testing in people. If serious problems are found in pre-clinical tests, a drug won’t be developed any further.

Clinical trials

If a drug passes all the pre-clinical tests, it can start being tested in people. Drug tests involving people are called clinical trials. Only a very small proportion of drugs make it as far as clinical trials.

Part of my reason for taking part in the trial was that I understand how important it is to get people involved in trials in order to have data to analyse.

Clinical trials are organised in phases. There are four different phases. Early phase trials (phase 1 or 2) involve small numbers of people. They make sure the drug is safe and find out the best dose to use. Later phase trials (phase 3 and 4) involve larger numbers of people and test whether or not a drug is effective. More is learnt about a drug as it goes through each phase. If a drug is not successful in one phase, it can’t go on to the next.

We have more detailed information about clinical trials, where we explain the different phases of clinical trials.

The clinical trial testing process usually takes several years, although this varies depending on the drug and the type of lymphoma it is being tested for.

Drug approval

If clinical trials are successful, the pharmaceutical company that produced the drug applies for it to be licensed (approved) for use. To do this, they have to provide evidence that the drug is safe and that it provides benefits for people with lymphoma. For example, it might improve outcomes, have a better side effect profile than current treatments, or be delivered in a more convenient formulation.

Your doctor can only give you treatments that have been officially approved (unless you are in a clinical trial). The approval process is designed to keep you safe and to make sure you only have treatments that are likely to benefit you.

Who approves new drugs?

Drug companies have to apply to different legal authorities in different parts of the world.

- The Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) approves drugs in the UK.

- The European Medicines Agency (EMA) approves drugs in the European Union. For 2 years following the end of the Brexit transition period on 1 January 2021, the UK will continue to adopt EMA approvals for drugs that it has not separately assessed.

Being approved is not the same as being available on the NHS. Approval means a drug can legally be prescribed. Once it has been approved, a drug is assessed separately to decide whether or not it will be available on the NHS.

Funding for NHS use

Once a drug has been approved, it is assessed by funding bodies in the UK to decide how well it works in relation to how much it costs. This is called a ‘health technology assessment’. It is used to decide whether or not the drug should be made available on the NHS.

In the UK, health technology assessments are conducted by independent organisations.

- The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) carries out health technology assessments in England. Wales and Northern Ireland also usually follow NICE guidance.

- The Scottish Medicines Consortium (SMC) carries out health technology assessments in Scotland.

- The All Wales Medicine Strategy Group (AWMSG) sometimes assesses drugs in Wales before a decision is reached by NICE. This is usually replaced by NICE guidance when it is available.

To make their decision, these organisations review all the evidence on the new drug and also gather input from a range of people, including healthcare professionals, people affected by the condition the drug is approved for, patient representative groups (such as Lymphoma Action), drug companies and independent health economic groups.

We have more information on how health technology assessments are carried out.

Listen to our podcast, Health Technology Assessment: NICE providing support to the NHS in the best way for the benefit of patients. In the podcast, Helen Knight, Director of Medicines and Evaluation at NICE talks about Health Technology Assessments and their role in making new treatments available through the NHS.

Listen to our podcast, Health Technology Assessment: NICE providing support to the NHS in the best way for the benefit of patients. In the podcast, Helen Knight, Director of Medicines and Evaluation at NICE talks about Health Technology Assessments and their role in making new treatments avaialble through the NHS.

How can I find out if a drug is available for me?

Each nation in the UK has a different way of funding cancer drugs. The websites for each of the health and technology assessment bodies have up-to-date information on which drugs are recommended and which are currently being assessed.

- If you live in England or Northern Ireland, visit the NICE website and search for the name of the drug you’d like to find out about. This will show you a list of assessments that are in progress as well as guidance that is already available.

- If you live in Scotland, visit the SMC website and search for the name of the drug you’d like to find out about. This will show you a list of guidance that is already available.

- If you live in Wales, visit the AWSMG website and search for the name of the drug you’d like to find out about. This will show you a list of assessments that are covered by NICE guidance and any separate assessments carried out by the AWSMG.

- If you live in Northern Ireland, visit the technology appraisal section of the NI Department of Health website. This lists all the NICE guidance that has been approved in Northern Ireland.

- You can also check our news section, where we report regularly on drug approvals and funding decisions for lymphoma treatments.

What if a drug I need isn’t available on the NHS?

First of all, talk to your consultant about what treatments are suitable for you. Even if a treatment has been approved for use in your type of lymphoma, it might not be right for you. Your consultant can give you advice based on your individual circumstances.

Occasionally, you might be able to access a treatment before it is available for routine use on the NHS. The main ways to do this are through the Cancer Drugs Fund or the Early Access to Medicines Scheme. In exceptional circumstances, your consultant might be able to apply for individual funding on your behalf.

The Cancer Drugs Fund

For new cancer drugs, NICE sometimes decides that although clinical trial results are promising, there is not yet enough evidence to recommend it for routine use. In this case, they might decide to make it available for a limited time – usually 2 years – while more evidence is being collected. They can do this through an NHS England scheme called the Cancer Drugs Fund (CDF). At the end of the time limit, the drug is assessed by NICE again to decide if it should be funded routinely on the NHS.

There is a central list of drugs available on the CDF. It gives details of the criteria that must be met to access each drug. The list is regularly updated and drugs can be added or removed. If your consultant feels a drug on the CDF list is appropriate for you, they can apply for you to have it.

The CDF is not available in Scotland, Wales or Northern Ireland.

The Early Access to Medicines Scheme

The Early Access to Medicines Scheme (EAMS) is a UK-wide scheme run by the UK Medicines and Healthcare Products Regulatory Agency (MHRA). It aims to give people with serious or life-threatening illnesses access to promising new drugs before they are licensed.

To be considered for the EAMS, a drug must have been tested in late phase clinical trials to find out if it is safe and effective. The MHRA assesses the clinical trial results to decide whether the benefits of the drug are likely to outweigh the risks. If so, they can recommend a treatment for the EAMS.

There are only a few drugs on the EAMS list at any time, but drugs for people with lymphoma are sometimes available through the scheme. They may only be available for a short period of time (usually up to a year) prior to approval. If you are eligible for a drug that is on the EAMS list, talk to your consultant to help you decide if it is the right option for you.

If a drug on the EAMS list becomes licensed, it goes through the usual appraisal process to decide whether or not it should be routinely available on the NHS. It is then taken off the EAMS list.

Other ways to access drugs that aren’t available on the NHS

In exceptional circumstances, if your medical team think you need a treatment that is licensed but is not routinely available on the NHS, they might be able to make an individual funding request for you. Applications for individual funding are reviewed by an independent panel including medical experts and members of the public. The panel decides if the treatment should be funded on an individual basis. Individual funding requests can only be made if your medical team can show that your clinical situation is so different to other people with the same type of lymphoma that you should have your treatment paid for when they would not.

If a drug is approved for your type of lymphoma but you are not able to get it on the NHS, you may be able to organise funding from alternative sources. Macmillan Cancer Support and Cancer Research UK have information on other things you could try.