Hairy cell leukaemia

This information is about hairy cell leukaemia, a slow-growing type of blood cancer. It also covers a condition known as ‘splenic B-cell lymphoma/leukaemia with prominent nucleoli’ or ‘hairy cell leukaemia variant’, which is treated as a type of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

On this page

Who gets hairy cell leukaemia?

Symptoms of hairy cell leukaemia

Relapsed or refractory hairy cell leukaemia

What is hairy cell leukaemia?

Hairy cell leukaemia is a slow-growing type of blood cancer. It develops when white blood cells called lymphocytes grow out of control. Lymphocytes are part of your immune system. They travel around your body in your blood and lymphatic system, helping you fight infections.

There are two types of lymphocyte: T lymphocytes (T cells) and B lymphocytes (B cells). B cells make antibodies which stick to proteins that the body recognises as foreign (antigens). T cells can either destroy cells in the body that are infected by antigens or activate other parts of the immune system to help. Hairy cell leukaemia develops from B cells.

In hairy cell leukaemia, the abnormal B cells build up in your blood and bone marrow. Occasionally, the abnormal B cells can build up in your lymph nodes.

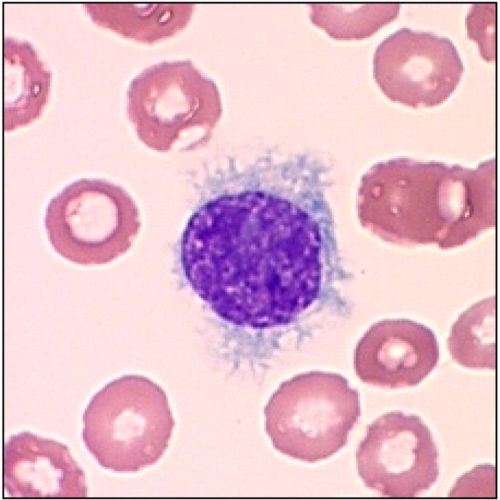

The abnormal B cells in hairy cell leukaemia look ruffled and hairy under a microscope. This is how it gets its name.

Who gets hairy cell leukaemia?

Hairy cell leukaemia is rare. Only around 230 people are diagnosed with it each year in the UK.

Hairy cell leukaemia affects around four times more men than women. It typically develops in middle-aged people. It is rare in young people.

There is no known cause of hairy cell leukaemia.

Symptoms

Some people have no symptoms when they are diagnosed with hairy cell leukaemia and it is found by chance when a blood test is done for another reason.

Most people develop symptoms slowly, as the number of abnormal cells grows.

It is common for these cells to build up in your bone marrow, where they take up the space needed for healthy blood cells to develop. This means your body might not be able to make enough blood cells and you might develop low blood counts, such as:

- anaemia (low red blood cells), which can make you feel tired, breathless or dizzy

- thrombocytopenia (low platelets), which makes you more likely to bruise and bleed

- neutropenia (low neutrophils – a type of white blood cell), which might make you develop infections more easily than usual, and can make it difficult to get rid of them

- monocytopenia (low monocytes – another type of white blood cell), which can increase your risk of developing infections.

It is also quite common for abnormal cells to build up in your spleen (an organ of your immune system). This can make your spleen swell, which can cause pain, discomfort, or a feeling of fullness in your tummy (abdomen). Your liver might also swell, which can cause bloating.

You might feel generally unwell, with symptoms like fatigue (extreme tiredness), weight loss, fevers and night sweats.

Rarely, people with hairy cell leukaemia develop swollen lymph nodes without having abnormal cells in their blood, spleen or bone marrow. This can look very similar to some types of low-grade (slow-growing or ‘indolent’) non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Very rarely, it can affect the bones as well as the bone marrow.

Diagnosis and staging

Hairy cell leukaemia can sometimes be diagnosed using blood tests. These typically show low blood counts together with abnormal ‘hairy’ lymphocytes in your bloodstream. The number of hairy cells in the blood can be very low and sometimes difficult to identify. You are likely to have a bone marrow biopsy to check for abnormal cells in your bone marrow.

An expert lymphoma pathologist looks at your blood and biopsy samples under a microscope. They run specialised tests on the abnormal cells to find out if they have certain genetic changes or make particular proteins.

Your doctor will also examine you to check for other signs of hairy cell leukaemia such as a swollen spleen or liver. You might have a scan, such as a CT scan or ultrasound scan, to see if your spleen is enlarged or if you have any swollen lymph nodes in your tummy (abdomen). However, a scan isn’t always necessary because these can often be detected on a physical examination.

You usually have your tests done as an outpatient. It takes a few weeks to get all the results. Waiting for test results can be a worrying time, but it is important for your medical team to have all the information they need so they can plan the most appropriate treatment for you.

Blood tests are also used to check your general health. If you are starting treatment, you might have blood tests to check if you have any viral infections that could flare up during treatment.

With most types of cancer, you are given a stage when you are first diagnosed. This tells you how widespread the cancer is in your body. For hairy cell leukaemia, there is no widely agreed staging system. Instead, your medical team use the results of your blood tests, physical examination and symptoms to decide whether or not you need treatment straightaway and what the best treatment is for you.

Outlook

Although treatment for hairy cell leukaemia is not curative, the outlook for hairy cell leukaemia is usually very good. Most people with hairy cell leukaemia have a normal life expectancy. Treatment is successful in most cases and usually puts the disease into remission (disappearance or significant shrinkage). Remission can last many years but hairy cell leukaemia usually comes back (relapses) and needs more treatment at some point. Nearly all people who relapse are treated successfully again.

Your medical team is best placed to advise you on your outlook based on your individual circumstances.

Treatment

The treatment you have for hairy cell leukaemia depends on how it is affecting you.

Active monitoring

You might not need treatment straightaway. This might be the case if you don’t have troublesome symptoms, your liver or spleen are not too swollen, and your blood counts aren’t too low. Instead, your medical team monitors you every 3 to 6 months until you need treatment. This is called active monitoring or ‘watch and wait’. This approach allows you to avoid the side effects of treatment for as long as possible.

If you are worried about your health at any time, contact your GP or medical team. You don’t have to wait for your next appointment.

You are likely to start treatment if:

- you develop symptoms such as fever, night sweats or fatigue

- your spleen, liver or lymph nodes become very swollen

- your blood counts become too low

- you have lots of infections or severe infections.

Treatment options

The most likely treatment for people with hairy cell leukaemia is chemotherapy. The most common chemotherapy drugs for hairy cell leukaemia are:

- Cladribine, which you have as an injection under your skin (subcutaneous injection) or through a drip into a vein (an intravenous infusion). Treatment is usually either given daily for up to 7 days, or once a week for 5 to 6 weeks.

- Pentostatin, which you have through a drip into a vein once every 2 to 3 weeks. You carry on having treatment until most of your blood counts return to normal levels, which is typically 4 to 5 months after starting treatment.

Very rarely, your medical team might recommend having an operation to remove your spleen (a splenectomy). This is usually only considered if your spleen is very enlarged and causing serious problems.

Your medical team will discuss the options with you to decide on the best course of treatment for you. They will also give you information about the typical side effects of the treatment they recommend. Macmillan Cancer Support have more information about cladribine and pentostatin and their possible side effects.

You have regular blood tests during and after treatment to check your blood counts. Around 4 to 6 months after treatment, you are likely to have a bone marrow biopsy. Your medical team uses the results of these tests to check how your hairy cell leukaemia has responded to treatment.

- Most people have a complete response to treatment. This means:

- your blood counts have returned to normal

- there are no abnormal cells in your bloodstream or bone marrow

- you no longer have a swollen liver or spleen.

- Some people have a partial response. This means:

- your blood counts have returned to normal

- there are no abnormal cells in your bloodstream

- your spleen and liver have shrunk by at least half

- and the number of abnormal cells in your bone marrow has reduced by at least half.

If you have a partial response to treatment, you might have another course of chemotherapy, sometimes combined with the antibody therapy rituximab. This increases your chance of having a long-lasting remission.

Treatment to relieve or prevent symptoms

As well as treatments to control the hairy cell leukaemia, you may have treatment to help relieve your symptoms or prevent infections. These might include:

- antibiotics and antiviral drugs to prevent or treat infections

- annual vaccinations against flu and pneumonia

- red blood cell transfusions or platelet transfusions to treat low blood counts (these have to be with specially irradiated blood products if you’ve had cladribine or pentostatin treatment, to prevent a reaction called ‘graft-versus-host disease’)

- growth factor (G-CSF) injections to boost your white blood cell count if you have an infection.

Contact your medical team straightaway if you have any symptoms of infection. It is important that you get prompt treatment.

Follow-up

When your hairy cell leukaemia is in remission after treatment, you have regular follow-up appointments. These might be at your hospital or at your local GP surgery. They are usually every 3 to 12 months.

At your appointment, you have blood tests and your doctor or nurse specialist examines you and asks if you have any concerns or symptoms. Your follow-up appointments are to check:

- how well you are recovering from treatment

- for any signs that the hairy cell leukaemia might be coming back (relapsing)

- that you are not developing any late effects (side effects that can develop months or years after treatment).

If you are worried about your health at any time, contact your GP or medical team. Don’t wait for your next appointment.

Relapsed and refractory hairy cell leukaemia

Treatment for hairy cell leukaemia is usually very effective and people often stay in remission for many years. However, hairy cell leukaemia often comes back (relapses) eventually, and needs more treatment. Occasionally, hairy cell leukaemia doesn’t respond well to your first treatment. This is called ‘refractory’ hairy cell leukaemia. It is usually treated the same way as relapsed hairy cell leukaemia.

The treatment you have depends on how long your remission lasted.

If you experience a relapse more than 2 years after your first treatment, you are likely to have the same treatment as you had before. This may be combined with an antibody therapy called rituximab.

If you experience a relapse less than 2 years after your first treatment, your medical team might recommend:

- a different chemotherapy drug, usually combined with rituximab – for example, if you had pentostatin as your first treatment, you are likely to have cladribine (plus rituximab) if you experience a relapse

- a different targeted drug as part of a clinical trial.

Occasionally, your medical team might recommend having an operation to remove your spleen (a splenectomy). This is usually considered only if your spleen is very enlarged and causing serious problems.

Research and targeted treatments

Standard treatments are usually very successful for hairy cell leukaemia. Clinical trials continue to test new treatments, most often for people with hairy cell leukaemia that is difficult to treat.

Scientists are testing many different targeted treatments in clinical trials, including some treatments that are already approved for other types of cancer. These include:

- BRAF-MEK pathway inhibitors, which slow or stop the growth of cancer cells

- B-cell receptor pathway inhibitors, such as BTK inhibitors, which block signals involved in the growth and survival of cancer cells

- Anti-CD22 immunoconjugates, which are antibody therapies joined to a toxin to target cancer cells

- BCL-2 inhibitors which activate the process of natural cell death

- CAR T-cell therapy, which involves genetically modifying your own T cells so they can recognise and kill cancer cells.

Some of these might be available to you through a clinical trial. If you are interested in taking part in a clinical trial, ask your doctor if there is a trial that might be suitable for you. To find out more about clinical trials or search for a trial that might be suitable for you, visit Lymphoma TrialsLink.

Hairy cell leukaemia variant

‘Hairy cell leukaemia variant (HCL-V)’ or ‘splenic B-cell lymphoma/leukaemia with prominent nucleoli’ is a very rare type of blood cancer that is similar to hairy cell leukaemia, although it’s actually a completely separate disease. Despite its name, it is often classed as a form of non-Hodgkin lymphoma.

Like classical hairy cell leukaemia, the abnormal cells in HCL-V look hairy under a microscope. The main difference is that the abnormal cells in classical hairy cell leukaemia have a genetic change called a BRAF mutation, but the abnormal cells in HCL-V do not.

Symptoms of HCL-V are similar to hairy cell leukaemia. However, unlike classical hairy cell leukaemia, HCL-V often causes very high white blood cell counts (leukocytosis).

As with hairy cell leukaemia, the treatment you have for HCL-V depends on how it is affecting you. If you do not have troubling symptoms, a period of active monitoring may be recommended. The most likely treatment for people with HCL-V is rituximab combined with chemotherapy (typically cladribine or pentostatin). Some people have surgery to remove their spleen (a splenectomy), if it is very enlarged.

HCL-V can be more difficult to treat than hairy cell leukaemia. If your HCL-V is refractory (doesn’t respond well to treatment) or relapses (returns after successful treatment) there are other treatment options, including targeted drugs as part of a clinical trial.